more evidence for my deeply held beliefs about *contests*

a very good read....

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703683804574533840282653628.html

<h1>A Hint of Hype, A Taste of Illusion

</h1><h2 ="sub">They pour, sip and, with passion and snobbery,

glorify or doom wines. But studies say the wine-rating system is badly

flawed. How the experts fare against a coin toss.</h2>

<h3 ="byline">By

LEONARD MLODINOW </h3>

Acting

on an informant's tip, in June 1973, French tax inspectors barged into

the offices of the 155-year-old Cruse et Fils Frères wine shippers.

Eighteen men were eventually prosecuted by the French government,

accused, among other things, of passing off humble wines from the

Languedoc region as the noble and five-times-as-costly wine of

Bordeaux. During the trial it came out that the Bordeaux wine merchants

regularly defrauded foreigners. One vat of wine considered extremely

inferior, for example, was labeled "Salable as Beaujolais to

Americans."

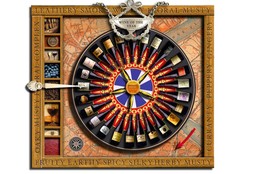

<div ="insetContent insetCol3wide - at-D"><div ="insetTree">

<div id="articleThumbnail_1" ="insettipUnit insetZoomTarget"><div ="insetZoomTarget"><div ="insettip"><div ="insettip">

<a>View Full Image</a><a>

</a>

<cite>Tia Gemmell/California State Fair</cite>

Wines are poured at the California State Fair wine competition in June 2008.

<div style="visibility: ;" id="article_1" ="insetFullBracket"><div ="insetFull"><div ="inset"><a ="inset">

</a>

It

was in this climate that in the 1970s a lawyer-turned-wine-critic named

Robert M. Parker Jr. decided to aid consumers by assigning wines a

grade on a 100-point scale. Today, critics like Mr. Parker exert

enormous influence. The medals won at the 29 major U.S. wine

competitions medals are considered so influential that wineries spend

well over $1 million each year in entry fees. According to a 2001 study

of Bordeaux wines, a one-point bump in Robert Parker's wine ratings

averages equates to a 7% increase in price, and the price difference

can be much greater at the high end.

Given the high price of wine and the enormous number of choices, a

system in which industry experts comb through the forest of wines,

judge them, and offer consumers the meaningful shortcut of medals and

ratings makes sense.

But what if the successive judgments of the same wine, by the same

wine expert, vary so widely that the ratings and medals on which wines

base their reputations are merely a powerful illusion? That is the

conclusion reached in two recent papers in the Journal of Wine

Economics.

Both articles were authored by the same man, a unique blend of

winemaker, scientist and statistician. The unlikely revolutionary is a

soft-spoken fellow named Robert Hodgson, a retired professor who taught

statistics at Humboldt State University. Since 1976, Mr. Hodgson has

also been the proprietor of Fieldbrook Winery, a small operation that

puts out about 10 wines each year, selling 1,500 cases

A few years ago, Mr. Hodgson began wondering how wines, such as his

own, can win a gold medal at one competition, and "end up in the

pooper" at others. He decided to take a course in wine judging, and met

G.M "Pooch" Pucilowski, chief judge at the California State Fair wine

competition, North America's oldest and most prestigious. Mr. Hodgson

joined the Wine Competition's advisory board, and eventually "begged"

to run a controlled scientific study of the tastings, conducted in the

same manner as the real-world tastings. The board agreed, but expected

the results to be kept confidential.

There is a rich history of scientific research questioning whether

wine experts can really make the fine taste distinctions they claim.

For example, a 1996 study in the Journal of Experimental Psychology

showed that even flavor-trained professionals cannot reliably identify

more than three or four components in a mixture, although wine critics

regularly report tasting six or more. There are eight in this

description, from The Wine News, as quoted on wine.com, of a Silverado

Limited Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon 2005 that sells for more than $100 a

bottle: "Dusty, chalky scents followed by mint, plum, tobacco and

leather. Tasty cherry with smoky oak accents…" Another publication, The

Wine Advocate, describes a wine as having "promising aromas of

lavender, roasted herbs, blueberries, and black currants." What is

striking about this pair of descriptions is that, although they are

very different, they are descriptions of the same Cabernet. One taster

lists eight flavors and scents, the other four, and not one of them

coincide.

<div ="insetContent insetCol3wide - at-D"><div ="insetTree">

<div id="articleThumbnail_2" ="insettipUnit insetZoomTarget"><div ="insetZoomTarget"><div ="insettip"><div ="insettip">

<a>View Full Image</a><a>

</a>

<cite>Photo illustration by Donna Kugleman/The Wall Street Journal; Getty Images (bottle); Alamy (puddle)</cite>

A smashed red wine bottle on white background.

<div style="visibility: ;" id="article_2" ="insetFullBracket"><div ="insetFull"><div ="inset"><a ="inset">

</a>

That

wine critiques are peppered with such inconsistencies is exactly what

the laboratory experiments would lead you to expect. In fact, about 20

years ago, when a Harvard psychologist asked an ensemble of experts to

rank five wines on each of 12 characteristics—such as tannins,

sweetness, and fruitiness—the experts agreed at a level significantly

better than chance on only three of the 12.

Psychologists have also been skeptical of wine judgments because

context and expectation influence the perception of taste. In a 1963

study at the University of California at Davis, researchers secretly

added color to a dry white wine to simulate a sauterne, sherry, rosé,

Bordeaux and burgundy, and then asked experts to rate the sweetness of

the various wines. Their sweetness judgments reflected the type of wine

they thought they were drinking. In France, a decade ago a wine

researcher named Fréderic Brochet served 57 French wine experts two

identical midrange Bordeaux wines, one in an expensive Grand Cru

bottle, the other accommodated in the bottle of a cheap table wine. The

gurus showed a significant preference for the Grand Cru bottle,

employing adjectives like "excellent" more often for the Grand Cru, and

"unbalanced," and "flat" more often for the table wine.

Provocative as they are, such studies have been easy for wine

critics to dismiss. Some were small-scale and theoretical. Many were

performed in artificial laboratory conditions, or failed to control

important environmental factors. And none of the rigorous studies

tested the actual wine experts whose judgments you see in magazines and

marketing materials. But Mr. Hodgson's research was different.

<div ="insetContent insetCol3wide - at-D"><div ="insetTree">

<div id="articleThumbnail_3" ="insettipUnit insetZoomTarget"><div ="insetZoomTarget"><div ="insettip"><div ="insettip">

<a>View Full Image</a><a>

</a>

<cite>Chris Wadden</cite>

<div style="visibility: ;" id="article_3" ="insetFullBracket"><div ="insetFull"><div ="inset"><a ="inset">

</a>

In

his first study, each year, for four years, Mr. Hodgson served actual

panels of California State Fair Wine Competition judges—some 70 judges

each year—about 100 wines over a two-day period. He employed the same

blind tasting process as the actual competition. In Mr. Hodgson's

study, however, every wine was presented to each judge three different

times, each time drawn from the same bottle.

The results astonished Mr. Hodgson. The judges' wine ratings

typically varied by ±4 points on a standard ratings scale running from

80 to 100. A wine rated 91 on one tasting would often be rated an 87 or

95 on the next. Some of the judges did much worse, and only about one

in 10 regularly rated the same wine within a range of ±2 points.

Mr. Hodgson also found that the judges whose ratings were most

consistent in any given year landed in the middle of the pack in other

years, suggesting that their consistent performance that year had

simply been due to chance.

Mr. Hodgson said he wrote up his findings each year and asked the

board for permission to publish the results; each year, they said no.

Finally, the board relented—according to Mr. Hodgson, on a close

vote—and the study appeared in January in the Journal of Wine

Economics.

"I'm happy we did the study," said Mr. Pucilowski, "though I'm not

exactly happy with the results. We have the best judges, but maybe we

humans are not as good as we say we are."

This September, Mr. Hodgson dropped his other bombshell. This time,

from a private newsletter called The California Grapevine, he obtained

the complete records of wine competitions, listing not only which wines

won medals, but which did not. Mr. Hodgson told me that when he started

playing with the data he "noticed that the probability that a wine

which won a gold medal in one competition would win nothing in others

was high." The medals seemed to be spread around at random, with each

wine having about a 9% chance of winning a gold medal in any given

competition.

To test that idea, Mr. Hodgson restricted his attention to wines

entering a certain number of competitions, say five. Then he made a bar

graph of the number of wines winning 0, 1, 2, etc. gold medals in those

competitions. The graph was nearly identical to the one you'd get if

you simply made five flips of a coin weighted to land on heads with a

probability of 9%. The distribution of medals, he wrote, "mirrors what

might be expected should a gold medal be awarded by chance alone."

Mr. Hodgson's work was publicly dismissed as an absurdity by one

wine expert, and "hogwash" by another. But among wine makers, the

reaction was different. "I'm not surprised," said Bob Cabral, wine

maker at critically acclaimed Williams-Selyem Winery in Sonoma County.

In Mr. Cabral's view, wine ratings are influenced by uncontrolled

factors such as the time of day, the number of hours since the taster

last ate and the other wines in the lineup. He also says critics taste

too many wines in too short a time. As a result, he says, "I would

expect a taster's rating of the same wine to vary by at least three,

four, five points from tasting to tasting."

<div ="insetContent insetCol3wide - at-D"><div ="insetTree">

<div id="articleThumbnail_4" ="insettipUnit insetZoomTarget"><div ="insetZoomTarget"><div ="insettip"><div ="insettip">

<a>View Full Image</a><a>

</a>

<cite>Tia Gemmell/California State Fair</cite>

Ribbons from the 2009 California State Fair wine competition.

<div style="visibility: ;" id="article_4" ="insetFullBracket"><div ="insetFull"><div ="inset"><a ="inset">

</a>

Francesco

Grande, a vintner whose family started making wine in 1827 Italy, told

me of a friend at a well-known Paso Robles winery who had conducted his

own test, sending the same wine to a wine competition under three

different labels. Two of the identical samples were rejected, he said,

"one with the comment 'undrinkable.' " The third bottle was awarded a

double gold medal. "Email Robert Parker," he suggested, "and ask him to

submit to a controlled blind tasting."

I did email Mr. Parker, and was amazed when he responded that he,

too, did not find Mr. Hodgson's results surprising. "I generally stay

within a three-point deviation," he wrote. And though he didn't agree

to Mr. Grande's challenge, he sent me the results of a blind tasting in

which he did participate.

The tasting was at Executive Wine Seminars in New York, and

consisted of three flights of five wines each. The participants knew

they were 2005 Bordeaux wines that Mr. Parker had previously rated for

an issue of The Wine Advocate. Though they didn't know which wine was

which, they were provided with a list of the 15 wines, with Mr.

Parker's prior ratings, according to Executive Wine Seminars' managing

partner Howard Kaplan. The wines were chosen, Mr. Kaplan says, because

they were 15 of Mr. Parker's highest-rated from that vintage.

Mr. Parker pointed out that, except in three cases, his second

rating for each wine fell "within a 2-3 point deviation" of his first.

That's less variation than Mr. Hodgson found. One possible reason: Mr.

Parker's first rating of all the wines fell between 95 and 100—not a

large spread.

One critic who recognizes that variation is an issue is Joshua

Greene, editor and publisher of Wine and Spirits, who told me, "It is

absurd for people to expect consistency in a taster's ratings. We're

not robots." In the Cruse trial, the company appealed to the idea that

even experienced tasters could err. Cruse claimed that it had bought

the cheap Languedoc believing it was the kingly Bordeaux, and that the

company's highly-trained and well-paid wine tasters had failed to

perceive that it wasn't. The French rejected that possibility, and 35

years ago this December, eight wine dealers were convicted and given

prison terms and fines totaling $8 million.

Despite his studies, Mr. Hodgson is betting that, like the French,

American consumers won't be easily converted to the idea that wine

experts are fallible. His winery's Web site still boasts of his own

many dozens of medals.

"Even though ratings of individual wines are meaningless, people

think they are useful," Mr. Greene says. He adds, however, that one can

look at the average ratings of a spectrum of wines from a certain

producer, region or year to identify useful trends.

As a consumer, accepting that one taster's tobacco and leather is

another's blueberries and currants, that a 91 and a 96 rating are

interchangeable, or that a wine winning a gold medal in one competition

is likely thrown in the pooper in others presents a challenge. If you

ignore the web of medals and ratings, how do you decide where to spend

your money?

One answer would be to do more experimenting, and to be more

price-sensitive, refusing to pay for medals and ratings points. Another

tack is to continue to rely on the medals and ratings, adopting an

approach often attributed to physicist Neils Bohr, who was said to have

had a horseshoe hanging over his office door for good luck. When asked

how a physicist could believe in such things, he said, "I am told it

works even if you don't believe in it." Or you could just shrug and

embrace the attitude of Julia Child, who, when asked what was her

favorite wine, replied "gin."

As for me, I have always believed in the advice given by famed food

critic Waverly Root, who recommended that one simply "Drink wine every

day, at lunch and dinner, and the rest will take care of itself."

<cite ="tagline">—Leonard Mlodinow teaches randomness at Caltech. His most recent book is "The Drunkard's Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives."</cite>