- Joined

- Nov 23, 2019

- Messages

- 486

- Reaction score

- 746

Gassing Regimens (link to original article)

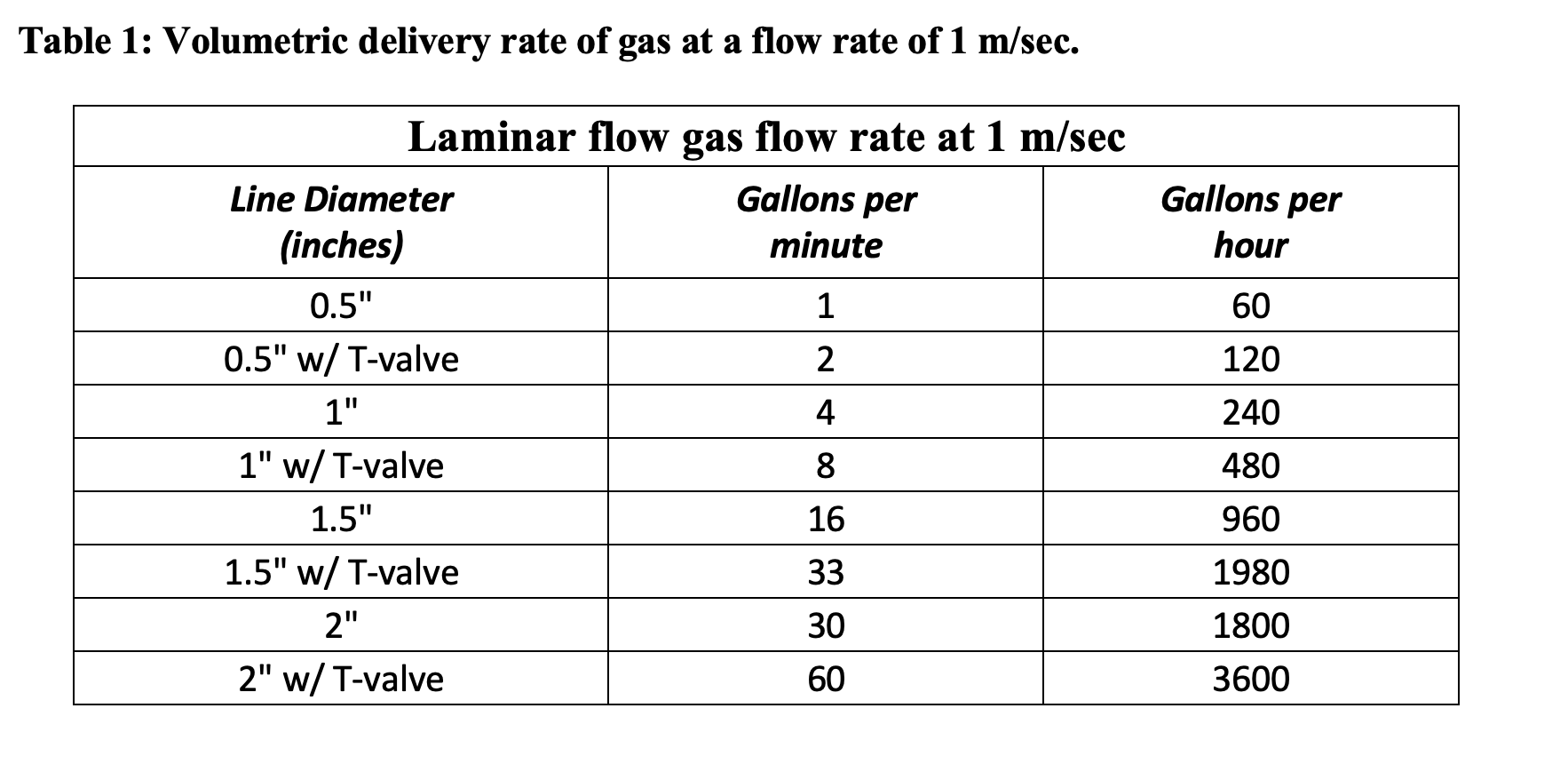

The winemaking process is a dynamic one: from crush, to fermentation, on to post fermentation cellar procedures, aging, and bottling. Each step along the way allows for the potential ingress of oxygen, whether wanted or not. While oxygen is considered by many to be the enemy of wine, this is not always the case. In fact proper use of enological oxygen at crucial steps in the winemaking process is paramount to wine development. That said, many winemakers dutifully aim to eliminate it from the process altogether particularly in partial tank headspace. Proper gassing regimens and selection of the correct gas for a particular application is something that many do not do well and fail to fully understand the principals at play. Managing proper inert gas procedures is tricky. Most protocols are generally arbitrary ones copied from bad information and the proliferation of poor techniques passed on anecdotally from winemaker to winemaker. In general it is a procedure that is often over looked and never given much thought. This usually means the use of a high pressure cylinder (most often nitrogen), and a ¼” or ½” hose that is allowed to run for an arbitrary amount of time, generally 15 to 20 minutes. The results are the improper use of inert gases from the failure to measure gas volumes delivered (using a flowmeter), monitoring results with the use of a dissolved oxygen meter, using an under or oversized delivery system and unsubstantiated cost analysis pertaining to gas type and volume needed.

Typical gas choices are: carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and argon. Most wineries choose to use carbon dioxide and nitrogen because they believe it provides the best cost-benefit in terms of oxygen displacement per unit cost. This is not the case. To understand this, we must first delve into some fundamental principles of gases. In the wine industry, we typically use gas by volume, either in standard cubic feet or molar volume delivered from a standard steel pressurized cylinder in which the gas is compressed. These gas volumes are usually measured at 25°C and 1 atm. If you happen to purchase gas by the pound it is necessary to divide the gas by its molecular weight before you can compare gases to one another. The approximate molecular weights are: 40 g/mole for argon (Ar), 44 g/mole for carbon dioxide (CO2), 28 g/mole for nitrogen (N2), and 29 g/mole for air. One mole of any of these gases measured at standard pressure (1atm) and temperature (25°C) occupies one molar volume, roughly equivalent to 22.4 liters, 5.92 gallons, or 0.8 standard cubic feet. Using the ideal gas law PV = nRT the behavior of gases can be described in which pressure and volume is a fixed proportion in relation to the number of moles of gas at absolute temperature. This indicates that gas molecules take up the same amount of space regardless of their mass when they are at the same temperature and pressure (Avogadro’s Law). Thus one mole of any gas contains the same number of molecules (i.e., 6.02 x 1023). This also indicates that the head space in a tank, barrel, or other container will fluctuate regularly throughout the day in response to temperature and pressure changes. Tanks that are kept outside experience greater temperature changes throughout the day compared to a tank kept inside at a constant temperature. Changes in barometric pressure and temperature can cause the headspace in a tank to pump 3% to 7% of its volume in and out daily. This ultimately means that the headspace in a tank is not a static system and could be constantly changing.

Air is roughly composed of 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, and 1% argon, so in essence nitrogen is air without the oxygen. In any gassing procedure it is ideal to reduce the percentage of oxygen in the headspace to below 1% or even below 0.5% to inhibit the growth of aerobic microbes and prevent wine oxidation. The most commonly used gas in winemaking is nitrogen (N2) with a molecular weight (MW) of 28 g/mole making it moderately lighter (less dense) than air at 29 g/mole MW. Graham’s law of diffusion (also known as Graham’s law of effusion) states that the rate of effusion of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of its molar mass at constant temperature and pressure. This principle is often used to compare the diffusion rates of two gasses such as nitrogen and air. The diffusion rates of nitrogen and air are almost identical meaning that nitrogen does not provide adequate layering, but rather readily mixes with air and does not remain in contact with the wine surface for an extended period of time. This also means that in order to reduce the O2level from 21% to less than 1%, the headspace needs to be flushed with a volume of nitrogen that is five times the volume of the headspace. So if the tank has a 100 gallons of head space it would take 500 gallons of nitrogen to reduce the O2level from 21% to below 1%. The cost of nitrogen is approximately $0.05 per cubic foot (Praxair, Inc). However, because nitrogen requires five times the volume equivalents to reduce the O2percentage from 21% to less than 1%, the cost to gas a barrel (60 gallons) is $2.00, 100 gallons of headspace is $3.34 and 1,000 gallons of headspace is $33.42. This is significantly higher than the cost of using argon for the same O2reduction in the equivalent headspace volumes. This is why headspace gassing with nitrogen requires a substantial effort and time commitment on the part of the winemaking team to be effective. It takes substantially more nitrogen and a greater application time compared to argon to achieve the same reduction in oxygen percentage with a shorter effective shelf life.

In contrast to nitrogen is carbon dioxide (CO2), which is significantly heavier than air at 44 g/mole compared to 29 g/mole and by Graham’s law has a much slower rate of diffusion compared to air. This allows for a more significant displacement of air compared to nitrogen. However, when CO2is delivered from a compressed tank, it is difficult to achieve the desired laminar flow necessary for successful layering. This results in substantial mixing of CO2and air. A more effective alternative for CO2delivery is dry ice (solid CO2) which leads to more efficient layering of CO2and subsequent displacement of air but does not form a permanent layer. However, it should be noted that CO2cannot be considered inert in the same way as nitrogen and argon. Because of Henry’s Law, which states that the solubility of a gas is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas above the solution, CO2readily dissolves into wine under standard conditions and its solubility can be increased or decreased with changes in pressure. This dissolution of CO2into the wine causes the pressure in the tank to fluctuate and results in the intake of air from the outside environment through an airlock to replace the lost volume of gaseous CO2. If there is no vacuum release valve on the tank, this could cause the tank to implode. Carbon dioxide dissolved in the wine will also alter the acid, flavor, and textural profile of the final wine. Carbon dioxide is much more effective when deployed early in the winemaking process at juice stage or when the wine is young as there will be substantial time to allow excess dissolved CO2to come out of solution. The use of dry ice to protect grape must is an effective way to protect wine must from excess oxygen exposure, deter fruit flies, and subsequently cool the must.

This leaves argon with a molecular weight of 40 g/mole, making it substantially heavier than air (29 g/mole) and similar in weight to CO2but more inert. A major opposition to the use of argon regularly in wine production is because it is significantly more expensive compared to the other two gases. It is true that when purchasing gas by volume argon is roughly three times as expensive as nitrogen or carbon dioxide. However it is much more effective at displacing air and creating a more permanent blanket that remains in contact with the wine surface longer while also remaining inert compared to CO2. Less volume is also needed to achieve the same desired results. At approximately $0.11 per cubic foot (Praxair, Inc) not including daily tank rental fee, a barrel (60 gallons) can be completely gassed with argon for $0.88, 100 gallons of head space for $1.47, and 1,000 gallons of headspace for $14.71. This cost is relatively insignificant to a winery’s bottom line in terms of the degree of quality preservation that argon can provide.

Gassing Regimens

By: Conor McCaney, Graduate Assistant, Department of Food Science & TechnologyThe winemaking process is a dynamic one: from crush, to fermentation, on to post fermentation cellar procedures, aging, and bottling. Each step along the way allows for the potential ingress of oxygen, whether wanted or not. While oxygen is considered by many to be the enemy of wine, this is not always the case. In fact proper use of enological oxygen at crucial steps in the winemaking process is paramount to wine development. That said, many winemakers dutifully aim to eliminate it from the process altogether particularly in partial tank headspace. Proper gassing regimens and selection of the correct gas for a particular application is something that many do not do well and fail to fully understand the principals at play. Managing proper inert gas procedures is tricky. Most protocols are generally arbitrary ones copied from bad information and the proliferation of poor techniques passed on anecdotally from winemaker to winemaker. In general it is a procedure that is often over looked and never given much thought. This usually means the use of a high pressure cylinder (most often nitrogen), and a ¼” or ½” hose that is allowed to run for an arbitrary amount of time, generally 15 to 20 minutes. The results are the improper use of inert gases from the failure to measure gas volumes delivered (using a flowmeter), monitoring results with the use of a dissolved oxygen meter, using an under or oversized delivery system and unsubstantiated cost analysis pertaining to gas type and volume needed.

Typical gas choices are: carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and argon. Most wineries choose to use carbon dioxide and nitrogen because they believe it provides the best cost-benefit in terms of oxygen displacement per unit cost. This is not the case. To understand this, we must first delve into some fundamental principles of gases. In the wine industry, we typically use gas by volume, either in standard cubic feet or molar volume delivered from a standard steel pressurized cylinder in which the gas is compressed. These gas volumes are usually measured at 25°C and 1 atm. If you happen to purchase gas by the pound it is necessary to divide the gas by its molecular weight before you can compare gases to one another. The approximate molecular weights are: 40 g/mole for argon (Ar), 44 g/mole for carbon dioxide (CO2), 28 g/mole for nitrogen (N2), and 29 g/mole for air. One mole of any of these gases measured at standard pressure (1atm) and temperature (25°C) occupies one molar volume, roughly equivalent to 22.4 liters, 5.92 gallons, or 0.8 standard cubic feet. Using the ideal gas law PV = nRT the behavior of gases can be described in which pressure and volume is a fixed proportion in relation to the number of moles of gas at absolute temperature. This indicates that gas molecules take up the same amount of space regardless of their mass when they are at the same temperature and pressure (Avogadro’s Law). Thus one mole of any gas contains the same number of molecules (i.e., 6.02 x 1023). This also indicates that the head space in a tank, barrel, or other container will fluctuate regularly throughout the day in response to temperature and pressure changes. Tanks that are kept outside experience greater temperature changes throughout the day compared to a tank kept inside at a constant temperature. Changes in barometric pressure and temperature can cause the headspace in a tank to pump 3% to 7% of its volume in and out daily. This ultimately means that the headspace in a tank is not a static system and could be constantly changing.

Air is roughly composed of 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, and 1% argon, so in essence nitrogen is air without the oxygen. In any gassing procedure it is ideal to reduce the percentage of oxygen in the headspace to below 1% or even below 0.5% to inhibit the growth of aerobic microbes and prevent wine oxidation. The most commonly used gas in winemaking is nitrogen (N2) with a molecular weight (MW) of 28 g/mole making it moderately lighter (less dense) than air at 29 g/mole MW. Graham’s law of diffusion (also known as Graham’s law of effusion) states that the rate of effusion of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of its molar mass at constant temperature and pressure. This principle is often used to compare the diffusion rates of two gasses such as nitrogen and air. The diffusion rates of nitrogen and air are almost identical meaning that nitrogen does not provide adequate layering, but rather readily mixes with air and does not remain in contact with the wine surface for an extended period of time. This also means that in order to reduce the O2level from 21% to less than 1%, the headspace needs to be flushed with a volume of nitrogen that is five times the volume of the headspace. So if the tank has a 100 gallons of head space it would take 500 gallons of nitrogen to reduce the O2level from 21% to below 1%. The cost of nitrogen is approximately $0.05 per cubic foot (Praxair, Inc). However, because nitrogen requires five times the volume equivalents to reduce the O2percentage from 21% to less than 1%, the cost to gas a barrel (60 gallons) is $2.00, 100 gallons of headspace is $3.34 and 1,000 gallons of headspace is $33.42. This is significantly higher than the cost of using argon for the same O2reduction in the equivalent headspace volumes. This is why headspace gassing with nitrogen requires a substantial effort and time commitment on the part of the winemaking team to be effective. It takes substantially more nitrogen and a greater application time compared to argon to achieve the same reduction in oxygen percentage with a shorter effective shelf life.

In contrast to nitrogen is carbon dioxide (CO2), which is significantly heavier than air at 44 g/mole compared to 29 g/mole and by Graham’s law has a much slower rate of diffusion compared to air. This allows for a more significant displacement of air compared to nitrogen. However, when CO2is delivered from a compressed tank, it is difficult to achieve the desired laminar flow necessary for successful layering. This results in substantial mixing of CO2and air. A more effective alternative for CO2delivery is dry ice (solid CO2) which leads to more efficient layering of CO2and subsequent displacement of air but does not form a permanent layer. However, it should be noted that CO2cannot be considered inert in the same way as nitrogen and argon. Because of Henry’s Law, which states that the solubility of a gas is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas above the solution, CO2readily dissolves into wine under standard conditions and its solubility can be increased or decreased with changes in pressure. This dissolution of CO2into the wine causes the pressure in the tank to fluctuate and results in the intake of air from the outside environment through an airlock to replace the lost volume of gaseous CO2. If there is no vacuum release valve on the tank, this could cause the tank to implode. Carbon dioxide dissolved in the wine will also alter the acid, flavor, and textural profile of the final wine. Carbon dioxide is much more effective when deployed early in the winemaking process at juice stage or when the wine is young as there will be substantial time to allow excess dissolved CO2to come out of solution. The use of dry ice to protect grape must is an effective way to protect wine must from excess oxygen exposure, deter fruit flies, and subsequently cool the must.

This leaves argon with a molecular weight of 40 g/mole, making it substantially heavier than air (29 g/mole) and similar in weight to CO2but more inert. A major opposition to the use of argon regularly in wine production is because it is significantly more expensive compared to the other two gases. It is true that when purchasing gas by volume argon is roughly three times as expensive as nitrogen or carbon dioxide. However it is much more effective at displacing air and creating a more permanent blanket that remains in contact with the wine surface longer while also remaining inert compared to CO2. Less volume is also needed to achieve the same desired results. At approximately $0.11 per cubic foot (Praxair, Inc) not including daily tank rental fee, a barrel (60 gallons) can be completely gassed with argon for $0.88, 100 gallons of head space for $1.47, and 1,000 gallons of headspace for $14.71. This cost is relatively insignificant to a winery’s bottom line in terms of the degree of quality preservation that argon can provide.